Shut that door

And what we should really get from age verification

In these days, in Australia anyone under 16 will lose access to the usual parade of social platforms: Snap, YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, etc.

Little by little, those companies will start poking at their users’ identities, watching for signs like device changes, behavioural patterns, or even a stranger’s report that a kid looks a little too kid-like.

When suspicion hits, the user will be nudged toward age checks, using a selfie, an ID, or even a payment card. If they fail, they’re suspended or removed. If platforms fail, they’re fined up to A$50 million.

The ruling comes from Australia’s eSafety Commissioner, but it isn’t some lone regulatory outburst.

In the US, 25 states have passed a form of age verification laws, with now discussions to have a federal regulation.

In the UK, the Online Safety Act blocks minors from platforms carrying adult or self-harm content. That covers obvious material, like porn, but also less obvious cases like Bluesky.

In the EU, France and Italy are imposing checks on porn sites, and several members of the European Parliament want a minimum age of 16 for social platforms, citing mental-health concerns.

After a few years of evidence of the potential risks of algorithmic-driven platforms (not only) for children, regulators are waking up.

Better later than never.

And that’s why now you may have seen a lot around age verification technologies. It is, though, a complex issue, especially from a technological perspective.

For one, there’s a difference between verification and estimation: the first tries to place someone precisely on the virtual timeline, the second just guesses whether you fall on the right side of a threshold.

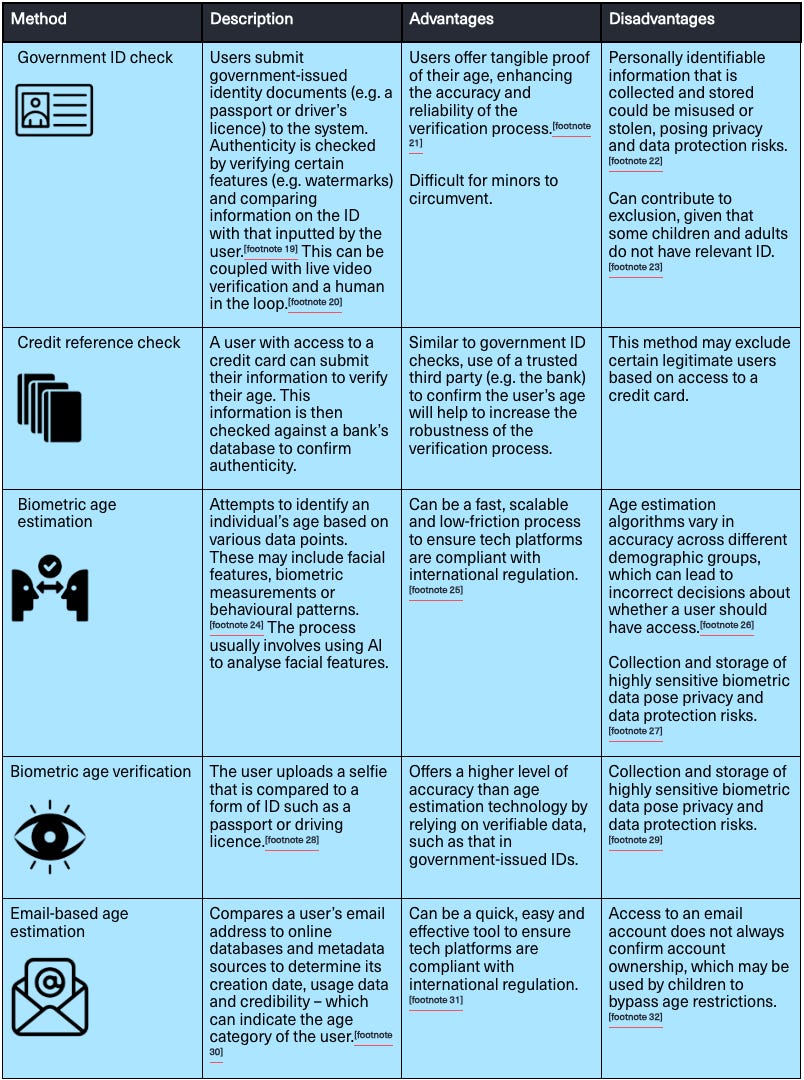

Multiple methods exist, each with its own tradeoffs:

A thriving market of third-party providers promises to help platforms comply, and somewhere down the line governments may issue digital wallets that let people prove their age more securely.

And none of the current techniques are flawless: from not recognising people with disabilities or belonging to minorities to not supporting who has no IDs (quite frequent in the US) to even questionable ways of storing personal and sensitive data.

To make matters worse, workarounds are popping up: in the UK, VPN usage among teens have spiked (no, kids are not all of a sudden wary of their IP secrecy) but also simply minors taking pictures of their parents on the first log-in.

All of this raises a few thorny questions.

At what level should age checks happen? Should every platform run or buy its own system, or should the app store handle it? Or maybe the device itself? No one seems particularly eager to own the problem.

And therefore, who is accountable if a children goes around the checks? Is it the social media platform or the external service used to verify the age? Or maybe the parents of the children that were not that attentive?

Still, the existence of loopholes doesn’t invalidate the purpose. Protecting minors from digital environments full of potential risks is a sensible, overdue ambition.

Yet - and this is the real purpose of this Artifacts - age verification goes far beyond minors.

All users will, in one way or another, need to prove their age. But, more importantly, this should make us think of what regulators are actually trying to protect all of us from: digital spaces that are, by design, likely to be risky.

In this sense, age verification is good, desirable, overdue - but also a bit of a smokescreen.

It’s a bit like preventing access to a building that may catch fire at any moment.

You can stop some people from entering, but we’re still not doing anything about the fire itself and the people who are already inside. Maybe they (we) should worry?

If a building is unsafe, we should be looking at its structure. The same is true for platforms: how do we prevent the fires that may come up?

It comes down to their design, and the risks this design carries. As simple as it sounds, digital harms stem from design decisions, namely policy choices with social consequences.

As raised by Mark Scott, if minors are not safe in accessing, then maybe we should be asking a question or two about the nature of these spaces in the first place.

And this is where age verification shouldn’t distract from the deeper issue.

What these regulatory shifts really point toward is design governance of online platforms. Not just more rules, but persuading who’s building platforms to take a step back.

This means asking very concrete questions: What incentives shape a platform’s architecture? What risks follow from those incentives? Why do those risks exist in the first place?

Maybe it’d be the moment to stop building algorithms for engagement - time spent, clicks - and think of user satisfaction. Perhaps time spent isn’t a positive signal at all, but the result of addictive design patterns.

And we could also ask more how much control users really have. How aware are they - not just minors, but everyone - of the algorithms that decide what keeps them scrolling?

Crucially, why not exploring alternatives to engagement-based recommendation models and give users more choice in what they see?

If platforms were truly providing beneficial, meaningful content, maybe we should even let minors use them more - why not? If value is what they get, why restrict access?

This is, intentionally, provocative. But it’s to underline a simple point: being in spaces where you have no control over what you see can be dangerous, regardless of your age. And of course, limited control is especially harmful for those who haven’t yet developed full awareness or confidence - which is why age verification is more than welcome.

Still, as the CEO of Patreon put it, “it is possible for algorithms to serve people instead of people serving algorithms.” That can happen only if we shift away from attention-based systems and towards designs that foster genuine human connection.

This would be a good start in thinking of architecture of these digital buildings.

If we followed through on that ambition, a few useful changes would kick in.

We would, for instance, start measuring signals like real user satisfaction, trust or the quality of connection created.

A system built on these principles would likely be more favourable to researchers, who could finally peek under the hood instead of guessing how these engines run.

And finally, instead of just shutting the door and keeping minors away, we’d end up constructing spaces where real literacy can happen because users have more control. With minors (and not only!) not just passive to algorithms suggesting things but actively involved in what information they consume.

To put it plainly, maybe the right way of looking at age verification is not the restriction itself but what it may hint at: access to spaces that need better design for users to be more in control and, thus, safer.

Save for Later

Why AI writes the way it does? But also how it may persuade voters, from Nature. Finally, how transparent are models, from Stanford.

European Tech seems to be getting better. And why censorship has very little to do with the fine of the EU Commission to X

How TikTok clusters the content you see. And also delivers some very bad stuff, it seems.

The Verge thinks we’re still far from good new browsers.

Recently watched a very cool movie on AI before it was a thing:

Where next?

Artifacts will be at the Political Tech Summit in Berlin 🇩🇪, 23–24 January 2026. Artifacts People in town, let’s say hi!

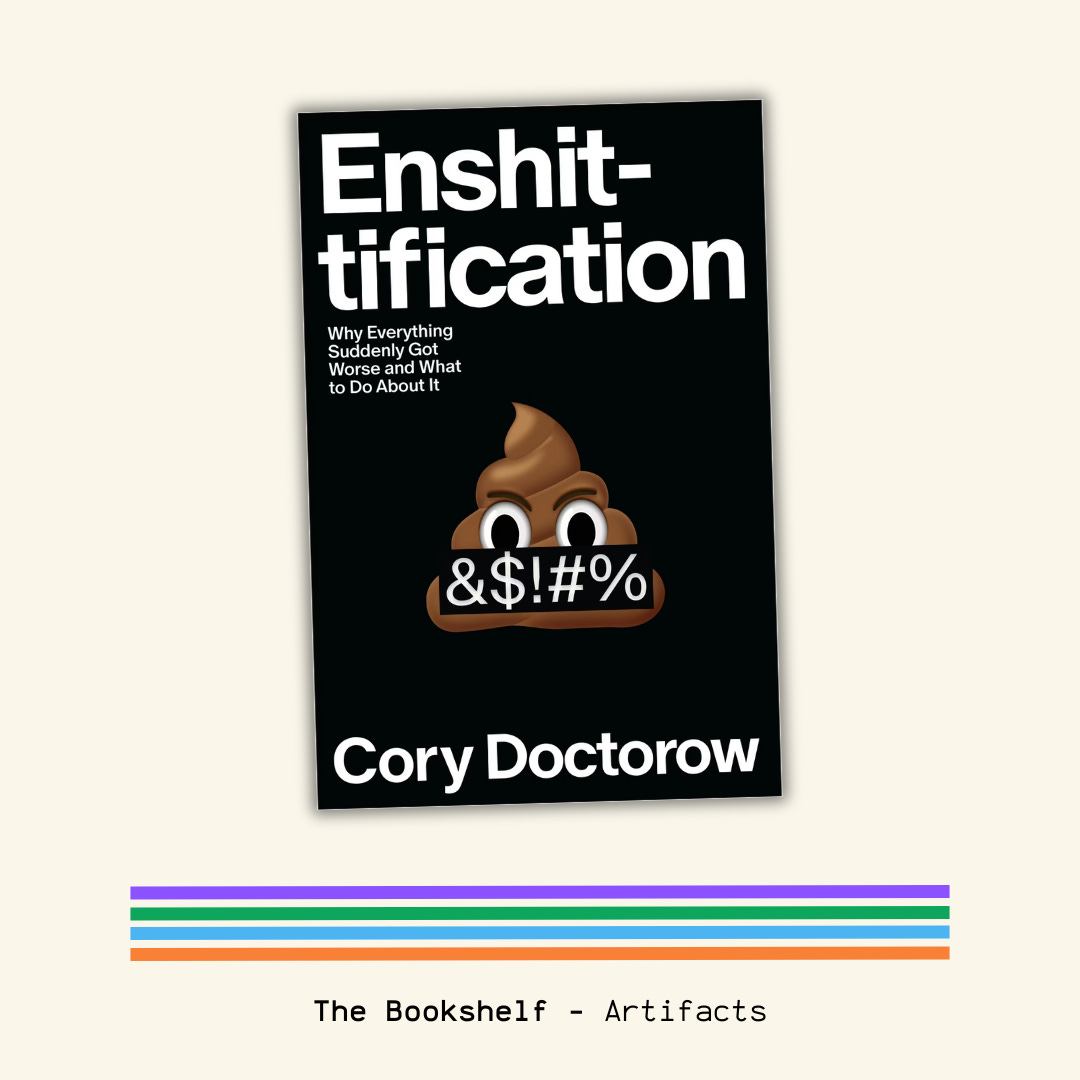

The Bookshelf

This one from Cory Doctorow will probably become a must-read on books about social media. It’s not about risks but more about the business models and why things are struggling to get better over time. Hence why, they’re getting enshittified.

📚 All the books I’ve read and recommended in Artifacts are here.

Nerding

Looks like we can’t help by building AI agents and this kind of stuff. Well, if properly done, they do help. If you want to get into some automation building, n8n is the go-to.

14 days free or completely free if self hosted!

☕?

If you want to know more about Artifacts, where it all started, or just want to connect...

The issue with the internet and social media is also anonymity. If I say or do certain things in real life I will face consequences but not if my social media handle protects me. Social media must be held accountable for what is said on the platforms, but so do users.

Verifying that users are real people is, therefore another crucial step going forward.

And, of course, changing the structure of incentives is the only way forward for social media, otherwise we will end up realising the dead internet theory, where no human content is published and it will only be AI bots -- which at the moment seems like a preferable alternative almost.