Pulling linchpins

What the Google vs DOJ case reveals about online search and, maybe, its future

“Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly[…]in general search services and search text advertising through a web of anticompetitive practices” declared Judge Mehta last August.

Some stats for perspective:

9 out of 10 online searches are conducted via Google.

Nearly 2 out of 3 internet users browse with Google Chrome.

It’s no wonder that “Googling” has become shorthand for browsing the web.

But the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) seems ready to rewrite the thesaurus. They’ve proposed a series of remedies aimed at dismantling what they describe as Google’s monopoly on digital search and advertising.

The DOJ’s wishlist of reforms is as ambitious as it is disruptive.

At the top of the docket is a headline-grabber: Google should sell Chrome, its flagship browser. The idea is simple—stop letting Google use its interconnected web of services to steer users deeper into its ecosystem.

But that’s not all. Google may also be expected to:

Share its treasure trove of user data with competitors, giving other search engines a shot at closing the quality gap.

Cease exclusive deals that keep Google Search preloaded on Apple devices and others.

Halt its acquisitions spree, which has often swallowed up competition before it can bloom.

Give advertisers more transparency and control over their campaigns.

And, in a nuclear scenario, sell Android if the softer measures don’t stick.

Once again (thinking of Microsoft in the 90s), competition policy is stepping in to fix (and try to break) entrenched structures. The aim? Forcing users and companies to imagine an Internet that is just different from the one we’re accustomed to.

Now, a looooot has been written and said on these solutions in the past weeks, especially on selling Chrome.

And many are the skepticals, pointing to several reasons: users would still gravitate back to Google even if it weren’t the default, that selling Chrome might just transfer monopoly power to its new owner, and that banning exclusive deals could threaten the survival of smaller browsers like Mozilla. The list goes on.

Yet, this Artifacts isn’t the space to weigh the pros and cons of those solutions.

Instead, we take a step back to ask bigger questions. Where are these ideas coming from? What do they reveal about the juggernaut Google has built? And most importantly, what do they hint at for the future of search and the internet at large?

The Story

Why Chrome? Because it’s more than a browser. It’s the linchpin, the gateway, the cornerstone, and the top of the funnel of the Google universe.

Open Chrome, and the gravitational pull begins. It nudges you to log in to your Google account (you don’t have to, but come on, you will), funnels you to Google Search, and then whisks you into Gmail, Docs, Maps, and beyond.

Chrome isn’t just software; it’s the operating system of your Google account. Sorry product managers :)

And, therefore, the problem is not Google Chrome itself, but what it represents and enables.

And that’s precisely why breaking up Chrome from Google, the DOJ argues, would shatter this synergy. A Chrome under new ownership wouldn’t have the same incentives to tie itself to Google’s broader services.

But Chrome is not the only linchpin of this alleged monopoly. There is something more, maybe less tangible and identifiable, that has been fuelling this monopoly: data

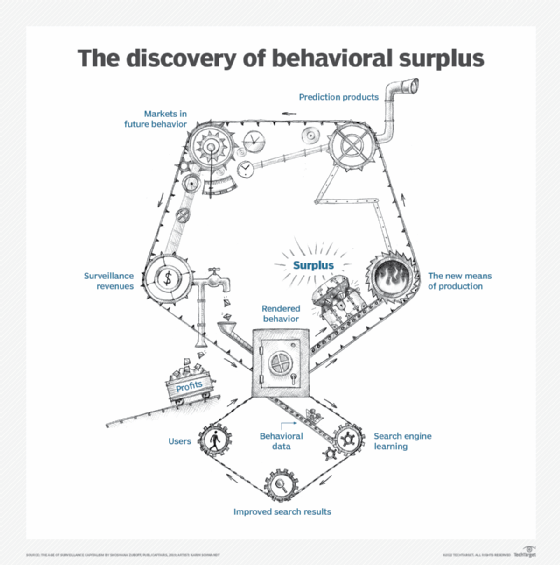

Google’s dominance is powered by two self-reinforcing feedback loops, straight out of Shoshana Zuboff’s Surveillance Capitalism:

User cycle (bottom): Google collects data to improve Search. Better Search attracts more users, who generate even more data, which further improves Search. Rinse, repeat.

Advertiser cycle (up): More users generate better targeting data, making Google the holy grail for advertisers. More ad dollars mean more resources for better services, which draw in yet more users.

The DOJ’s remedies aim squarely at the first cycle, the one below.

By forcing Google to share its data hoard with rivals, the hope is that alternative engines—think Bing or DuckDuckGo—won’t lag behind due to Google’s outsized head start.

Instead of playing catch-up on raw search quality, they could focus on differentiators like privacy or user experience. Concretely, they could focus on building features of a search engine instead of a search engine from scratch.

In theory, it’s a chance for competitors to finally get a foot in the door.

Since data at scale is the essential raw material for “building, improving and sustaining” a competitive general search engine, the DOJ now aims to force Google to make this data available and at disposal of other engines.

Ultimately, the DOJ’s goal is plain: crack open the search market—or, if you’re feeling cynical, break up Google and cross your fingers that a fairer ecosystem emerges from the rubble.

But fairer for whom? At first glance, the answer seems obvious: competitors like Bing, DuckDuckGo, and other underdog search engines. Yet, as is often the case, the reality is more nuanced.

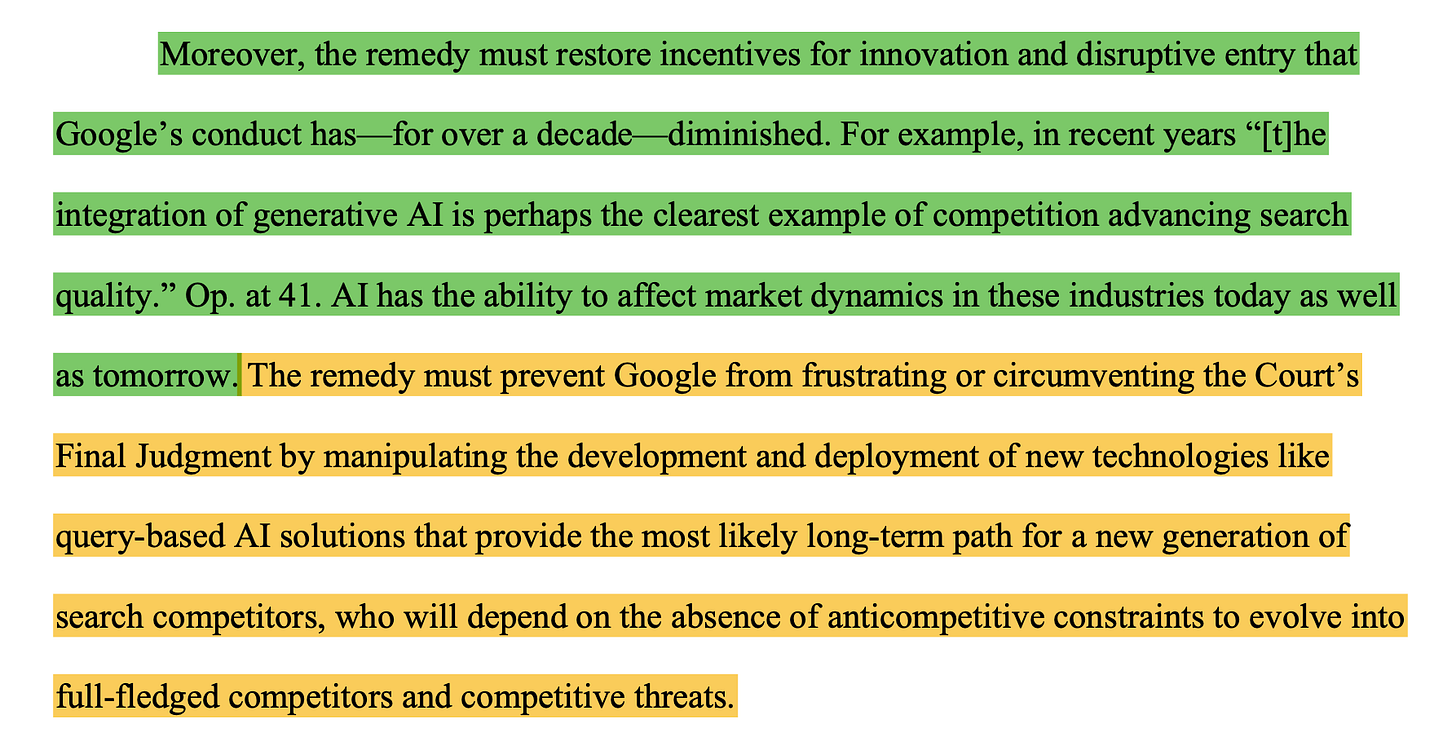

Interestingly, the DOJ’s proposals look beyond traditional search engines. The plaintiffs have pointed to “query-based AI solutions” as the next big thing.

As seen earlier, ChatGPT with a Search plugin, Perplexity, Arc—these conversational, AI-powered tools could represent the future of how we search online.

If search is shifting from ten blue links to AI-driven dialogues, then the remedies need to make room for that transformation.

The goal is not just to dethrone Google, but to foster innovation and ensure the search landscape evolves.

Of course, this is all a big “if.” The DOJ’s proposals are just that—proposals. The final ruling isn’t expected until next summer, and Google will appeal any decision it doesn’t like.

Regardless of the outcome, the DOJ’s case is a rare glimpse into the mechanics of Google’s dominance and, indirectly, how it managed to get that big.

For now, one thing is certain: “Googling” isn’t fading away anytime soon. But its grip on the internet? That’s about to face its toughest test yet.

Save for Later

How is Europe doing on tech? A few numbers and a lot of charts from a VC

Why we could’t vote online. And what Big Tech CEOs want from a second Trump presidency. Oh, Russia blatantly interfered with the US elections.

Teaching with ChatGPT, straight from OpenAI. And how ChatGPT made the US elections a bit better!

What an AI-curated web may look like, by Perplexity. Which is also rolling out ads in its tool.

Why disinformation is a thing coming from the many.

What does it mean to moderate the online space? Moderators spoke up.

A rundown of the 100 iconic technologies from Hard For. Must listen!

🟢 Join the Artifacts Community on WhatsApp to get other Save for Later content!

Someone said this before

“If the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail.” - Abraham Maslow

The Bookshelf

For a deeper dive into the inner workings of Google, Steven Levy’s In The Plex is an essential read. Written a few years back, it offers a sharp and detailed look at how Big G thinks and operates. Levy, with his knack for storytelling and tech insight, is the perfect guide to unravel this tale.

📚 All the books I’ve read and recommended in Artifacts are here.

Nerding

If you’re into tech, you’ve probably heard of DuckDuckGo — the privacy-focused browser that’s been taking on Chrome over the past few years. If safeguarding your personal data matters to you (and you’re curious about what search results look like without tracking), it’s worth giving it a shot.

☕?

If you want to know more about Artifacts, where it all started, or just want to connect...